Breaking the silence of genital mutilation

Published: Monday, July 05, 2010

The Irish Times - Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Greater awareness among healthcare workers in Ireland is needed to help women who have undergone 'female circumcision', writes CATHERINE REILLY

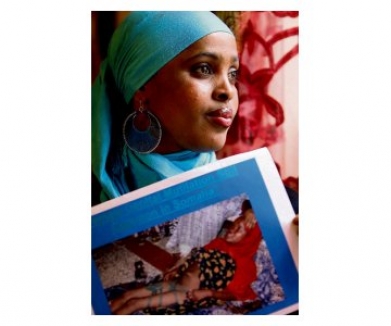

A WINNING SMILE fails to conceal 19-year-old Amina's* horrific burden, one that can render her bed-bound for days at the asylum seeker hostel in Co Galway where she lives.

Aged six, her family sanctioned a local "circumciser" in her native Somalia to mutilate her genitals, and the consequences reverberate across time and place and within mind, body and soul. When her period comes, it feels as though "the cutting" is happening all over again.

"Oh my God the pain, you are afraid of the pain," says the teenager, her neat hijab framing a welcoming face. "I am like, 'Oh my God, let it not come, let it not come'."

She endures chronic stress, frequent infections, back pain and is anaemic, all likely traceable to that watershed day when she was mutilated alongside three other girls.

More than 2,500 migrant women in Ireland are estimated to have suffered some form of female genital mutilation (FGM) in their countries, according to AkiDwA, a national network of African and migrant women.

Social customs, control over female sexuality, marriageability and religion (although no faith obliges FGM) are commonly cited motivators behind a practice usually carried out by local women using basic items like blades and scissors.

FGM is most prevalent in Africa, with vast country-to-country variations: it's very common in Egypt, Sierra Leone and Guinea, for example, yet quite rare in Cameroon and Uganda.

It involves partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons, says the World Health Organisation (WHO), which defines four main types.